Pests are commonly described in horticulture as insects that eat or damage plants. Pests can also refer to all pathogenic organisms that affect plants including diseases (rusts, smuts, pythium and armillaria). Pesticides as a consequence refer to a chemical or substance that controls all pest organisms including diseases and insects. This is an abridged article on insect pests; the complete article is on the website. An article on diseases will appear in a later newsletter.

For many years we assumed that all insects were bad and we sprayed our gardens to kill them all. in the past 20 years there has been a significant shift towards treating them on a case by case basis. This is known as Integrated Pest Management (IPM) and is managing pests with cultural, biological or chemical means. you can manage the insects in your garden by using IPM.

The first thing you must know is what sort of pest it is. If you are unsure, you can ask at the Australian national Botanic Gardens or your local nursery. And remember, some insects in our gardens are beneficial and actually feed on the bad pests.

The Goodies

Green Lace Wings - as the name suggests they are green and have clear wings. Females lay up to 600 eggs in clusters on a small stalk to protect them from ants. The larvae feed on aphids, mites, mealy bugs and white fly.

Lady Birds - lay their eggs in the egg mass of common pest insects like mealy bug. When the eggs hatch, the larvae immediately begin feeding on the host eggs.

Some Baddies - Sap Suckers

Scale - there are several species varying from a small round dome to clusters of 'cocoons', protected by a crusty surface. If the population is low and the plants aren't stressed, leave them; if it is high, apply a pest oil, e.g white oil, to coat the leaf surface and suffocate the scale.

Psyllids (Lerps) - small insects with sugary crusty coating for protection. Can have an impact on eucalypts if in large populations. Control can be difficult when in upper branches. If numbers are low, don't worry but monitor. If spraying is required use a pest oil to 'smother' them.

Spittle bug - nymphs attach to leaves using mouthparts and suck, producing foamy liquid 'spittle', formed by air being taken into abdominal channel and expelled through anus, forming bubbles. Bugs are rounded, slightly dome-shaped, 10mm long. Nymphs resemble adults but lack wings. Control not necessary if in low numbers. If damage is seen, then spray with a pest oil or Confidor*.

Aphids - small pear shaped, green insects; can occur in large populations. Have wide range of hosts, exotics and many natives, e.g Chrysocephalum apiculatum, orchids such as Thelychiton and grevilleas. Best not to spray if in small numbers as they are food for the Goodies. If damage (leave discolouration) is occurring, control with a pest oil, soapy water, some soap insecticides or Confidor*.

Mealy bug - found above and below ground so can attach roots of indoor plants without being seen. Are small, 'woolly' and white and move slowly on leaves and branches, but if numbers are high they look like a mass of white fluffy material. If populations are low they are food for ladybird lavae. If numbers are high, control first with pest oil,then an insecticide, Confidor* or Folimat**.

More Baddies - Leaf Eaters

Cup Moth - named after cocoon like structure it pupates in. Adults are small moths, 4 cm long. Lay eggs in clusters on eucalypt, melaleuca, guava and apricot leaves. When hatched many larvae feed on the same leaf; as they mature, they get a leaf each. Have retractable spines as a defense, which sting if touched. Best control : remove with gloved hand and squash with a sturdy foot.

Processionary Caterpillars - small hairy caterpillars that move in a line along branches or leaves. Hairs can irritate if touched. The affect eucalypts and some Acacia species. Some species bind leaves together to form a 'nest', which they eventually eat; can then defoliate whole trees. If numbers are low, best control is to remove them with a gloved hand and squash with a sturdy foot.

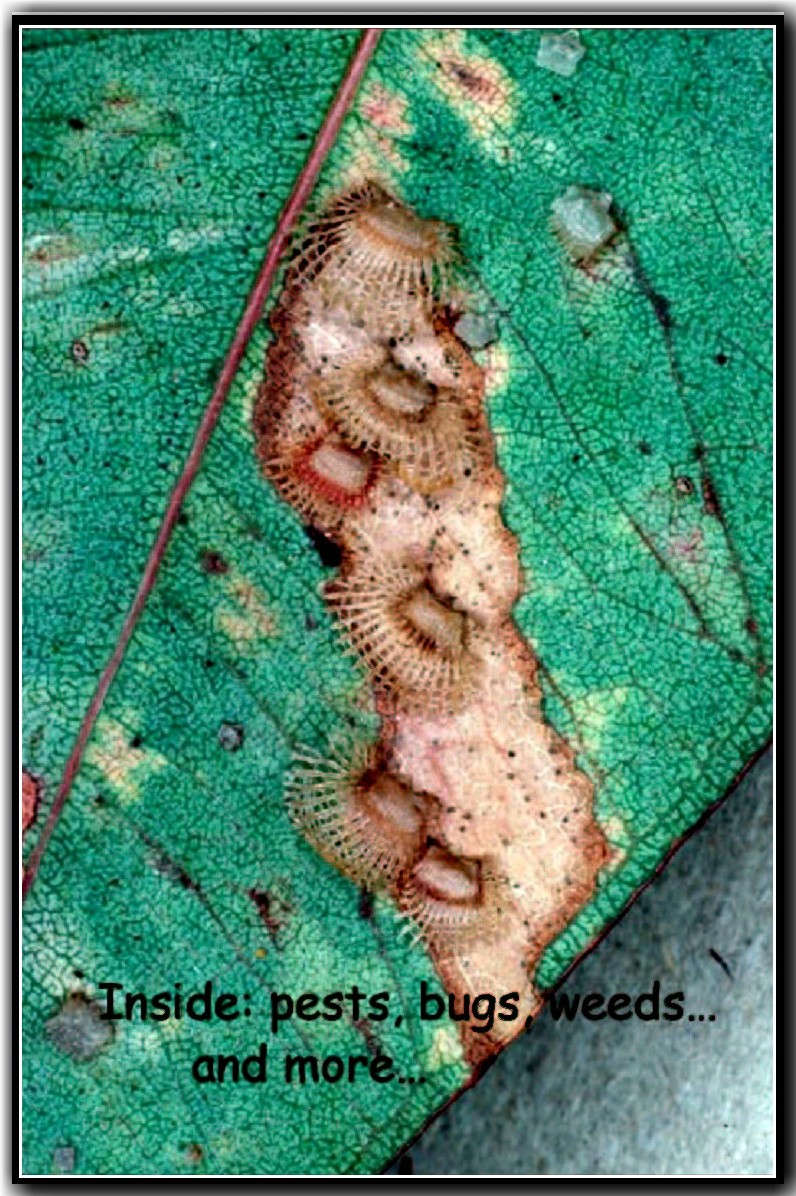

Steel Blue Sawfly Larvae - 'spitfires', as they spit a substance that irritates open wounds and/or eyes. The larvae do the damage; can defoliate entire eucalypt trees in several weeks. Best control : knock them from the tree (if within reach) and squash them with a sturdy foot.

Christmas Beetles - largish beetle, about 20mm long, present in large numbers in summer. Adults feed on eucalypt leaves; can cause severe defoliation if lots of them. The larvae develop in the soil, eating decaying organic matter or plant roots, causing plants to wither and turn yellow. Adults emerge in spring and fly to the nearest food plant to feed and mate.

* Confidor is a pesticide that is purchased as an aerosol. It is convenient as no mixing is required

but protective equipment (gloves, mask, overalls) must be worn.

** Folimat is an aerosol pesticide, easy to spray on small infected areas but protective equipment

(gloves, mask, overalls) must be worn.

*

* * *

*