In

September 1994 a small population of trees of a previously unknown type

was discovered growing in a secluded gorge in Wollemi National Park,

150 km west of Sydney. Subsequent investigation of its leaf, pollen,cone

and seed morphology indicated it to be a new species in a new genus

within the Araucariaceae family. Its pollen and leaf style was then

matched with fossils from 94 to 2 million years ago and this led to

the conclusion that it once had a widespread geographic range that included

Tasmania, New Zealand, India, Antarctica and southern South America.

The surprise discovery

of fewer than one hundred trees of a type thought to be long extinct,

growing undetected close to the largest city in Australia, attracted

world-wide attention in the media. The genus was named Wollemia

in reference to its occurrence in Wollemi National Park and the species

became nobilis to honour its discoverer David Noble (a NSW Parks

and Wildlife Service ranger who found the tree while bushwalking). Wollemia

nobilis soon became commonly known as the 'Wollemi pine'.

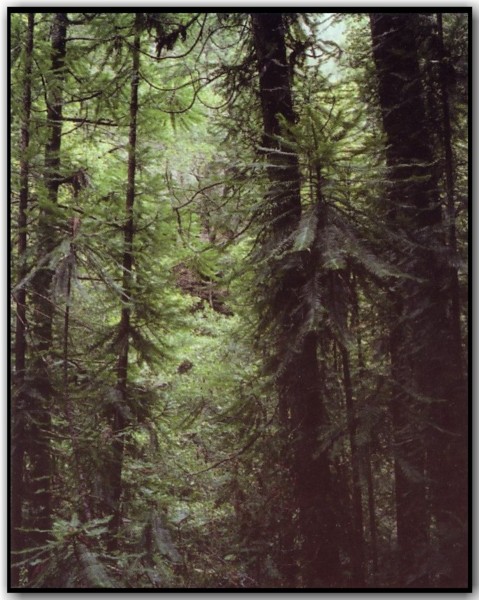

Wollemi

Pine trees, some more than 30 metres in height,

growing on site in Wollemi National Park

Photo

courtesy of Roger Heady

Although a definite

member of the Araucariaceae family, Wollemia nobilis has several

unique features. Mature trees often develop many stems after the original

trunk has died. This is termed 'coppicing' and is very unusual for a

conifer. It also has very distinctive bubbly bark that was described

as being "like coco-pops" by David Noble. Also its leaves

are unusual in having no mechanism for being shed from the tree after

they die. Instead leaves are removed when the tree sheds the entire

branch.

Scientific investigation

of the generic makeup of Wollemia nobilis has produced the surprising

conclusion that there is no genetic variability between the 100 or so

individual adult trees and 200 seedlings that are now known to occur

in three separate sites within the park. This is indicative of a species

that is on the verge of extinction and is probably a result of inbreeding

within a very small population.

Examination of

the tree rings of a fallen tree on site has indicated that the age of

some trees can be greater than 300 years. The occurrence of a 'wind

shear' in the wood of the tree also indicates that very strong winds

occasionally occur within the gorge. Examination of the wood of Wollemia

by scanning electron microscopy has shown that it is similar in its

micro-anatomy to that of the other two Araucariaceae genera, Agathis

and Araucaria.

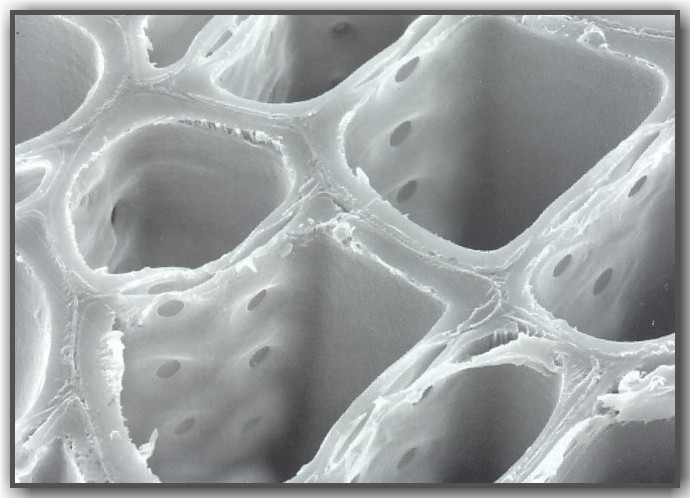

A

scanning electron microscope image of a very small area of the wood

of Wollemi Pine.

The sample is about 0.08 millimetre in width and shows an end-on view

of

several tube-like tracheids which transport water from the roots

up to the leaves of the tree.

The

small inner apertures are

bordered pits that inter-connect tracheids to one another.

The particular arrangement of these bordered pits indicates that

Wollemia belongs in the Araucariaceae family.

Photo

courtesy of Roger Heady

After at least two million years

in decline, and with so few remaining specimens, the Wollemi Pine trees

growing in the wild are definitely teetering on the verge of extinction.

The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service and Royal Sydney Botanic

Gardens have devised plans to protect the remaining trees and ensure

long-term species survival. It was realised that the site must not become

a popular tourist attraction and to ensure this the exact location f

the trees within Wollemi National Park remains a closely guarded secret.

Access to the site is limited to the absolute minimum, and those who

are admitted must adhere to strict regulations. Great care is taken

that seedlings are not trampled. Anti-microbial footbaths are used to

ensure plant diseases are not introduced, and in order to reduce soil

compaction, visits to individual trees are minimised. Sites are monitored

to ensure that there are no visits, either by chance or otherwise, by

bushwalkers or plant collectors.

Furthermore, in order to conserve

the species, a plan to propagate trees on a commercial scale has been

devised. It is hoped that by making Wollemi Pine trees widely available

to the public that the risk of illegal and potentially devastating collection

of the species in the wild will be reduced. Commercially grown Wollemi

Pine trees will become available in September 2005. Persons wanting

to be placed on a waiting list to buy a plant should register at

http://www.wollemipine.com.

Experiments at the Royal Sydney Botanic Gardens

have indicated that the juvenile Wollemia grows well in pots,

and can make a nice feature tree for large gardens. It favours acidic

(ph 4.5) soils and is very tolerant of shade.